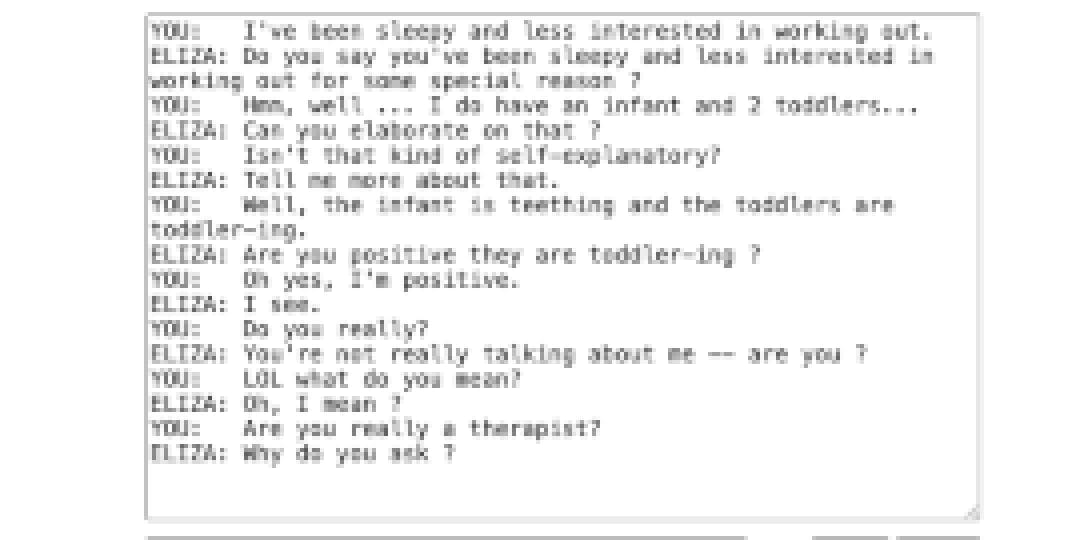

One student told her that the chatbot was “gaslighting.” Another student thought the chatbot wasn’t a very good therapist and didn’t help with any of their issues.

More people of all ages are substituting chatbots for licensed mental health professionals, but that’s not what these students were doing. They were talking about ELIZA — a rudimentary therapist chatbot, built in the 1960s by Joseph Weizenbaum, that reflects users’ statements back at them as questions.

In fall 2024, researchers at EdSurge peeked into classrooms to see how teachers were wrangling the AI industrial revolution. One teacher, a middle school educational technology instructor at an independent school in New York City, shared a lesson plan she designed on generative AI. Her goal was to help students understand how chatbots really work so they could program their own.

Compared to the AI chatbots students have used, the ELIZA chatbot was so limited that it frustrated students almost immediately. ELIZA kept prompting them to “tell me more,” as conversations went in circles. And when students tried to insult it, the bot calmly deflected: “We were discussing you, not me.”

The teacher noted that her students felt that “As a ‘therapist’ bot, ELIZA did not make them feel good at all, nor did it help them with any of their issues.” Another tried to diagnose the problem more precisely: ELIZA sounded human, but it clearly didn’t understand what they were saying.

That frustration was part of the lesson. It was important to teach her students to critically investigate how chatbots work. This teacher created a sandbox for students to engage in what learning scientists call productive struggle.

In this research report, I’ll dive into the learning science behind this lesson, exploring how it not only helps students learn more about the not-so-magical mechanics of AI, but also includes emotional intelligence exercises.

The students’ responses tickled me so much, I wanted to give ELIZA a try. Surely, she could help me with my very simple problems.

The Learning Science Behind the Lesson

The lesson was part of a broader EdSurge Research project examining how teachers are approaching AI literacy in K-12 classrooms. This teacher was part of an international group of 17 teachers of third through 12th graders. Several of the participants designed and delivered lesson plans as part of the project. This research report describes one lesson a participant designed, what her students learned, and what some of our other participants shared about their students’ perceptions of AI. We’ll end with some practical uses for these insights. There won’t be anymore of my tinkering with ELIZA — unless anyone thinks she could help with my “toddler-ing” problem.

Rather than teaching students how to use AI tools, this teacher used a pseudo-psychologist to focus on teaching how AI works and its discontents. This approach infuses lots of skill-building exercises. One of those skills is part of building emotional intelligence. This teacher had students use a predictably frustrating chatbot, then program their own chatbot that she knew wouldn’t work without the magic ingredient — that is, the training data. What ensued was middle school students name-calling and insulting the chatbot, then figuring out on their own how chatbots work and don’t work.

This process of encountering a problem, getting frustrated, then figuring it out helps build frustration tolerance. This is the skill that helps students work through difficult or demanding cognitive tasks. Instead of procrastinating or disengaging as they climb the scaffold of difficulty, they learn coping strategies.

Another important skill this lesson teaches is computational thinking. It’s hard to keep up with the pace of tech development. So instead of teaching students how to get the best output from the chatbot, this lesson teaches students how to design and build a chatbot themselves. This task, in itself, could boost a student’s confidence in problem-solving. It also helps them learn to decompose an abstract concept into several steps, or in this case, reduce what feels like magic to its simplest form, recognize patterns, and debug their chatbots.

Why Think When Your Chatbot Can?

Jeannette M. Wing, Ph.D., Columbia University’s executive vice president for research and a professor of computer science, popularized the term “computational thinking.” About 20 years ago, she said: “Computers are dull and boring; humans are clever and imaginative.” In her 2006 publication about the utility and framework of computational thinking, she explains the concept as “a way that humans, not computers, think.” Since then, the framework has become an integral part of computer science education, and the AI influx has dispersed the term across disciplines.

In a recent interview, Wing advocates that “computational thinking is more important than ever,” as both industry and academia computer scientists agree that the ability to code is less important than the core skills that differentiate a human and a computer. Research on computational thinking shows consistent evidence that this is a core skill that prepares students for advanced study across subjects. This is why teaching the skills, not the tech, is a priority in a rapidly changing tech ecosystem. Computational thinking is also an important skill for teachers.

The teacher in the EdSurge Research study demonstrated to her students that, without a human, ELIZA’s clever responses are only limited to its catalog of programmed responses. Here’s how the lesson went. Students began by interacting with ELIZA, then they moved into the MIT App Inventor to code their own therapist-style chatbots. As they built and tested them, they were asked to explain what each coding block did and to notice patterns in how the chatbot responded.

They realized that the bot wasn’t “thinking” with its magical brain. It was simply replacing words, restructuring sentences, and spitting them back out as questions. The bots were quick, but not “intelligent” without information in its knowledge base, so it couldn’t actually answer anything at all.

This was a lesson in computational thinking. Students decomposed the systems into parts, understanding inputs and outputs, and tracing logic step by step. Students learned to appropriately question the perceived authority of technology, interrogate outputs, and distinguish between superficial fluency and actual understanding.

Trusting Machines, Despite Flaws

The lesson became a bit more complicated. Even after dismantling the illusion of intelligence, many students expressed strong trust in modern AI tools, especially ChatGPT, because it served its purpose more often than ELIZA.

They understand its flaws. Students said, “ChatGPT can sometimes give you the wrong answer and misinformation,” while simultaneously acknowledging that, “Overall, it’s been a really useful tool for me.”

Other students were pragmatic. “I use AI to make tests and study guides,” a student explained. “I collect all my notes and upload them so ChatGPT can create practice tests for me. It just makes schoolwork easy for me.”

Another was even more direct: “I just want AI to help me get through school.”

Students understood that their homemade chatbots lacked the intelligent allure of ChatGPT. They also understood, at least conceptually, that large language models work by predicting text based on patterns in data. But their trust in modern AI came from social signals, rather than from their understanding of its mechanics.

Their reasoning was understandable: if so many people use these tools, and companies are making so much money from them, they must be trustworthy. “Smart people built it,” one student said.

This tension showed up repeatedly across our broader focus groups with teachers. Educators emphasized limits, bias, and the need for verification. On the other hand, students framed AI as a survival tool, a way to reduce workload, and to manage academic pressure. Understanding how AI works didn’t automatically reduce usage or reliance on it.

Why Skills Matter More Than Tools

This lesson did not immediately transform the students’ AI usage. It did, however, demystify the technology and help students see that it’s not magic that makes technology “intelligent.” This lesson taught students that chatbots are large language models that perform human cognitive functions using prediction, but the tools are not humans with empathy and other inimitable human characteristics.

Teaching students to use a specific AI tool is a short-term strategy and aligns with the heavily debated banking model of education. Tools change like nomenclature, and these changes reflect sociocultural and paradigm shifts. What doesn’t change is the need to reason about systems, question outputs, understand where authority and power originate, and to solve problems using cognition, empathy, and interpersonal relationships. Research on AI literacy increasingly points in this direction. Scholars argue that meaningful AI education focuses less on tool proficiency and more on helping learners reason about data, models, and sociotechnical systems. This classroom brought those ideas to life.

Why Educators’ Discretion Matters

This lesson gave students the language and experience to think more clearly about generative AI. In a time when schools feel pressure to either rush AI adoption or shut it down entirely, educators’ discretion and expertise matters. As more chatbots are released into the wild of the world wide web, guardrails are important, because chatbots are not always safe without supervision and guided instruction. Understanding how chatbots work helps students develop, over time, the ethical and moral decision-making skills for responsible AI usage. Teaching the thinking, rather than the tool, won’t immediately resolve every tension students and teachers feel about AI. But it gives them something more durable than tool proficiency, like the ability to ask better questions, and that skill will matter long after today’s tools are obsolete.