Sometime during his junior year at University of Missouri, Philip Hickman hung up the football pads and decided to pad his résumé. On those four pages are six degrees, countless certificates, and a recognition by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology as a #GoOpen ambassador for his use of open educational resources.

The former aspiring linebacker credits his professors for inspiring him to think about careers beyond the gridiron. “I went to college on a football scholarship. But in my sophomore year I had a professor who took a liking to me and asked, ‘So what graduate school are you going to?’”

“It was not an opportunity I had realized was possible,” Hickman recalls. He majored in psychology and took a liking to speech pathology, volunteering at the local Boys and Girls Club during his free time. He then went on to study school psychology and special education in graduate school.

His parents’ background was another source of influence. His mother taught in schools. His father, a UPS employee, bought computers from wealthier families and brought them home for Hickman and his older brother to play with. They were fortunate to enroll in computer classes, learning DOS and basic programming. These experiences—or rather, the “collision of human learning and computers,” as he describes it—inspired him to pursue a career in education technology.

Opportunities to learn about careers paths and technology were not always available to his students at Columbus Municipal School District in Mississippi, where he’s served as superintendent since July 2014. More than 80 percent of the students quality for free and reduced lunch—a glaring indicator of low-income households. Like many former Southern manufacturing hubs, the area suffered economic downturn and unemployment when factories shuttered or left in the early 2000s. Some are returning; high-tech manufacturing companies such as Stark Aerospace have set up shop.

Yet the education system, says Hickman, isn’t adequately preparing students for these opportunities. “These companies would have 60 to 70 positions open a month, unfilled, because people were coming out of school with skills that weren’t prepared for these jobs.”

Throughout his career as a school psychologist, counselor, principal, professor, company founder and, prior to his current job, assistant superintendent at Houston Independent School District, “the most important thing is giving kids access to and having role models,” Hickman tells EdSurge. He likens this mission to model cars. “A kid can have all the pieces and all the instructions. But you never know when you’re finished until you look at the picture on the box to see what the car looks like.”

We caught up with Dr. Hickman to learn more about his district’s progress, headaches, and what it takes to find the right technologies for the students—and tactfully get the buy-in and resources to support these investment. This interview has been edited for clarity.

EdSurge: How are you working to close the opportunity gap?

Hickman: Our children of poverty have less of an opportunity to have access to information, to technology, to experiences that can shape a student’s mindframe and career ambitions. Technology can be a great equalizer. Although we couldn’t physically take our kids to a lot of different places, we can take them to a lot of different places mentally by opening up their minds to technology.

What progress are you most proud of?

When I came here two years ago, we had a 60 percent high school graduation rate. We now have about 80 percent.

What are these career pathways that you’ve implemented in your district?

There are five magnet schools in the elementary levels—a school for arts, aerospace and engineering, medical science, international studies, and technology. What we built in was a kind of project-based learning where kids not only have book knowledge, but also learn about real-life activities relevant to that profession and also meet professionals who do such work.

For instance, if I’m in kindergarten, maybe I’ll learn about the heart and other body parts and make clay replicas. Later on I’ll meet a nurse and a doctor. But by fifth grade I should understand more specific science and medical related careers, maybe something like biotechnology or biochemistry, and be aware of these other professions. We use resources from Project Lead The Way [a nonprofit that provides STEM curriculum and lesson plans to schools] and Naviance [an online tool to help students plan and prepare for college and career skills].

At the middle school, students create personal graduation plans and choose from one of five “Future Pathways” [STEM, Business and Industry, Arts and Humanities, Public Services, Multi-Disciplinary]. They continue with these plans in high school, and throughout this time they have a virtual portfolio that captures their projects that they can show to any college or university. The hope is that our kids will then be recruited, just like athletes are recruited in certain fields.

How did you find resources to support buying these tools?

When I first started, on July 28, 2014, the superintendent before me had ordered close to a million dollars’ worth of textbooks. They had no correlation to the standards that we had just switched to, which was Common Core. So to me, they were just kind of useless.

At my first board meeting, I said that we have to take back all these textbooks. And I told them that I didn’t know if we’re going to get our money back, but I can’t use the books. You can imagine that the media ran me through the ringer all the way until January.

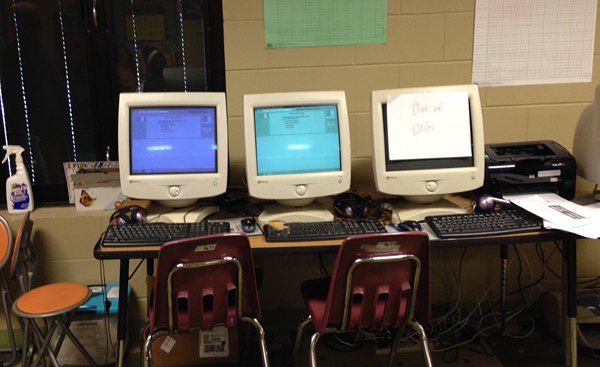

Fortunately I got most of the money back—around $800,000. I repurposed that money and purchased around $800,000 worth of technology. At the time we had Gateway computers—the ones with the real large monitors. We’re now 1:1 with MacBooks at our high school, with some HP devices. At the middle school we have HPs and iPads, and iPads in the elementary schools.

Do you encounter hurdles when trying to get buy-in from the local community—the parents and the board, for instance—for big tech purchases? How do you handle them?

In wealthier districts, we didn’t have to have as much conversation because we had a bring-your-own-device policy, since most kids already had one. And most parents kind of understood the need for learning software. But the further you go into the lower socio-economical environments, and especially where resources are more stressed, [the local community] can be opposed to large budget items for devices and software. In my district I was scrutinized for every software that I wanted to purchase.

We did a lot of town hall meetings. We also trained parents to talk to parents who are not able to come to school board meetings at those weird hours. We have to be mindful that we have a new generation: the working poor, families that are working 16, 18 hours a day just to maintain poverty level. We need them as partners in order to help support what we’re doing with technology, and what it looks like when their child comes home.

We also had to train teachers to not just use technology as they had traditionally; for example, point-and-click games. They have to help students understand how to use technology—to explore, research and gain information to broaden their horizons, and not just play games.

Any advice for other school leaders to make smart purchasing decisions, given all the new online services and tools available today?

You have to know what your kids need. One of the things that I do every time when I partner with a company is ask them to look at our data, listen to our feedback, and see if they can adjust the product to fit our population. The product may have worked for another group of students but our population of kids is different.

Another aspect is professional development. We don’t want just a sit-and-get professional development … but rather support folks who come into our buildings and are coaching. They should help with implementation—that the tools, devices and software are being used correctly within our curriculum in our classrooms. If companies are not doing that, then we weed them out.

The last thing is not to be afraid to have flexible contracts. I’ve entered into a lot discussions and said, “This is a pilot so we’re going to see how it works this far, and if it’s not working, we’re going to ask to terminate the contract.” So we change the language of our contracts. And if people are confident in their software or their tools, which they should be, then they shouldn’t have a problem with that.

What’s your biggest headache these days?

Once our kids leave our building, many still lack access to ongoing technology and Wi-Fi. We tried to mitigate that, so we put Wi-Fi on the buses, park them in neighborhoods and make it available in our local parks. We mapped [these locations] for our families so they know to also take their kids there. But it’s still not enough for kids to have the anywhere, anytime access to digital experiences that other kids in more affluent neighborhoods are. It’s frustrating.