Each year at the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival, there’s a group of filmmakers who need their parents’ permission to attend their own movie premieres.

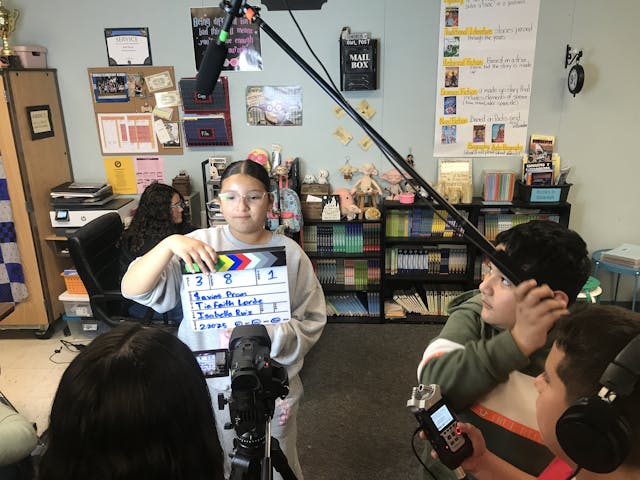

They’re part of the Youth Cinema Project affiliated with the Latino Film Institute, where students in fifth through 12th grade spend a school year writing, shooting and editing a short film.

The true goal of the program is not to produce filmmakers, Latino Film Institute CEO Axel Caballero says. The Youth Cinema Project currently has about which currently has about 2,000 student participants in several dozen classes across 16 California school districts.

Rather, the aim is to use hands-on activities to grow all of the skills that students need both in school and on a film set — and Caballero says they’re seeing results in both test scores and social skills. Scripts have to be written and revised, same as English papers. Directors and assistant directors have to keep the filming on schedule, like any group project leader. Everyone on set has to communicate clearly and calmly.

“They're guided through that process of being able to see what the written word could then become in a visual manner,” Caballero says. “That includes everything from character development to conflict and the act structure, to how you're going to shoot something and think about it ahead of time, what's good storytelling versus not good storytelling. One thing is to read it on paper, and the other thing is, will that be conveyed in a visual manner to the person watching the short?”

The program is an interesting approach to growing students’ literacy and social-emotional skills at a time when recent federal data shows that reading scores continue to decline and students struggle with attention.

Connection to Academics

Schools have told Caballero that students who go through the program have better test scores — from 10 percent to 30 percent higher — because, he says, they become more vocal and active participants during class.

He also says the program is also a boon to students who are learning second languages, including helping those learning English catch up and move on from ESL classes more quickly.

“We’re seeing as kids advance at a much quicker pace, at least that’s what some of the districts and classes are reporting,” Caballero says. “That they begin performing or assessing their language skills and tests at a much higher level after YCP. Again, all the things combined — from storytelling techniques to social-emotional learning to a collaborative environment — [play] into that.”

Then there’s an added layer for students at dual-language schools who have to do the whole process in a second language.

That’s the process at Dos Caminos Dual Immersion School, where principal Sarah Zepeda says seventh grade is the time when students are expected to ramp up their fluency. The school has participated in the Youth Cinema Project since 2017, and its students write and film completely in Spanish.

“It sparks their creativity, it allows them to work collaboratively with their peers, it really unites our group,” she says. “They’re not just sitting, learning Spanish in class. Our students also have a very high percentage of passing the AP Spanish test when they leave here, whether they're in the [film] program or not, but certainly, the program allows them the confidence to be able to even think about taking the Advanced Placement Spanish test once they get to high school.”

Finding Their Creative Spark

Last year was the first time eighth grader Victor Vallejo walked the red carpet at the famous Chinese Theatre in downtown Los Angeles, where the film he had written and directed was making its debut at the annual Latino film festival.

As a student at the school where Zepeda is principal, he had to write his script in Spanish, and his class selected the screenplay as the one they wanted to film and edit.

“It was an amazing experience,” says Vallejo, who is working on another script as part of his second year in the Youth Cinema Project. “Being able to express creativity through art, writing, directing it alongside my friends was fun. We got to walk the red carpet, take photos and see it on the big screen.”

The nearly yearlong process of creating the movie was no simple feat, says mentor Gabriela Acevedo. Known as “Ms. Gaby” to her students, says that she talks with the students at length about grit and determination because the filmmaking process is hard, especially for her seventh and eighth grade dual-language school students who are learning Spanish. They are script writing, acting, and communicating completely in Spanish, and it's tough even for students who speak Spanish at home.

Acevedo says the program also forces students to become a team through the filming process. While she is there to teach students about each role on a film set and guide them, they have to grow into their roles and hold each other accountable.

For example, students only have 90 minutes to film twice per week, including setting up and taking down the equipment. Lollygagging puts them behind schedule, and the assistant director has to be comfortable keeping time and pushing their peers to work efficiently.

Students write in the fall and film in the spring. Before the winter break, they vote on which script from the class will go into production the following semester.

Acevedo says many students struggle with the screenwriting process in part because they don’t believe their experiences are important enough to write about.

“We had a student who moved to California from Latin America,” Acevedo says. “She was struggling to make friends and speak English, so she wrote a story about that, and the class chose that [script to produce]. The whole class kind of rallied for her, and I hope she was able to make friendships.”

The themes of the students’ films vary, but Acevedo says the most commonly recurring one is bullying. Scary films and sports movies are also favorite genres, she adds.

“I do think that regardless of where they are, a lot of teenage worries are universal,” Acevedo says.