If you’re launching a new SEL program or enhancing an existing one, these tips will help you avoid common implementation mistakes.Tamara Alston expects her students to hold her accountable if she’s not being respectful and “solving problems in a way that works” for the community. And they do.

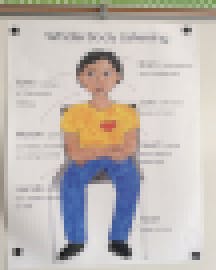

This is an element of “whole body listening,” a practice of respectful and attentive listening all students learn at the fifth grade teacher’s school, Hazel Wolf K-8 STEM in Seattle. “Whole body listening” is just one part of the school’s approach to and emphasis on social and emotional learning.

Alston says Hazel Wolf takes a top-down approach to SEL. The school has a Wolf Pack Pact, a set of five guidelines for the school community:

- We focus on learning

- We respect ourselves and others

- We take care of our school

- We solve problems

- We PERSEVERE!

Her school expects all that all teachers use the Wolf Pack Pact, as well as the Caring School Community curriculum (for grades K-5) or the lessons from the “MindUP” books—to build their classroom communities in the first few weeks of school. MindUP is the primary resource for grades 6-8, although fifth graders use it as well, and some K-4 teachers use it for some of the mindfulness lessons.

Alston points to a time when her students held her accountable. About a month ago, the class had a meeting to discuss bringing students’ lunch bags back to the room after lunch.

“Our current system wasn’t working. Kids were starting to blame each other and were all around just upset,” Alston describes. “They called a class meeting to address the issue and come up with some solutions to try out, which they did. They set a deadline for when I was supposed to check to see how things were going, and I forgot. Kids reminded me that I didn’t do my part, so they put the item back on the agenda.”

Melissa Schlinger, the Vice President of Practice and Programs at CASEL, tells EdSurge that teachers holding themselves accountable, as Alston does in her classroom, is vital for building a positive, SEL-friendly school culture. She adds that creating that type of culture starts with stakeholders developing a shared vision for what they want the school to be like for both adults and kids.

Schlinger adds that “there’s no question” that a school’s principal is “one of the most critical factors” in creating a school with a “positive climate” and a focus on social and emotional learning.

“We’ve seen schools where teachers are doing great work in their classrooms, but it can only really go so far,” she says. She believes that principals need to be “publicly committed to” SEL.

But the principal should not be the only voice, she explains. Teachers, she says, need to be part of decisions on SEL implementation. Teachers also need to think about how to intentionally build relationships with not only students, but other adults in the building. CASEL recommends that a school has an SEL team that has a “diverse group of stakeholders,” including the principal, a couple of teachers, an “out of school time” provider, a parent and possibly a student—depending on the age group the school serves.

Social-emotional skills support student achievement, but embedding SEL into the school day can be complex.

If you’re launching a new SEL program or enhancing an existing one, these tips will help you avoid common implementation mistakes.

On a broader level, a school’s culture and climate “has as much to do with, if not more to do with, the adults” as it does with how it supports students, she says. Adults at a school should build relationships with and appreciate each other, feel part of the community and agree on how they want to interact with each other and with students.

She points to a school in Chicago she loves visiting. One of the “norms” at Marcus Garvey Elementary School is that when adults and kids pass by each other in the hall, they acknowledge each other by name. If they don’t know the name of the other person, staff and students are encouraged to introduce themselves. The adults, she says, are modeling “an appropriate way to positively interact with others.”

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a custodian, a security officer, the principal, a parent—whoever it is, there’s an acknowledgment and eye contact,” Schlinger says. “You can really feel the difference in a school like that where adults are acknowledging each other and creating that environment, versus a school where people walk through the halls and barely make eye contact, or no one actually knows the custodian’s name, or the deans are met with contempt because they’re the disciplinarians.”

Schlinger believes that schools should conduct a “needs and resources inventory” before taking on the task of building an SEL-friendly culture. According to Schlinger, schools should think about what structures, programs and resources they already have in place that they can leverage, and build on those. They should also consider what their greatest needs are, and think about the data they want to “move the needle on,” such as too many suspensions for students of color.

Schlinger also says a common obstacle schools encounter when they consider incorporating SEL curriculum might “boil down to budget issues.” Districts, she explains, need to support principals and teachers with adequate budgets, coaching or programming.

“Principals can do this on their own,” she says. “But the most effective models are when you have a superintendent in a central office staff who really understands how to do this throughout the district in a supportive way.”

Schlinger also points to another potential barrier; overwhelmed principals and teachers who are crushed for time may view SEL as “one more thing to do” as opposed to something that’s “pivotal to their bigger mission.” She stresses that a focus on SEL is “in fact the rocket fuel needed for improvements in academics and student outcomes.”

Seattle’s Alston has similar thoughts. She says that because she and other teachers spend a lot of time at the beginning of the year building their classroom communities, there’s a foundation for those times when the class encounters difficulties or needs to persevere through teaching and learning difficult concepts. Without that initial SEL work, she explains, it doesn’t matter how good a teacher’s lessons and units are. Kids need to feel like they can take risks, and need to be in a community of trust, self-reliance and cooperative learning.

"Teaching is hard for teachers and it’s hard for kids," Alston says. “And learning is difficult. But if you’ve established a way that we can figure this out together, then it helps you get through the hard parts.”