As anyone who’s ever spent time in a classroom knows, teachers are constantly generating ideas and implementing them with their students. Naturally, schools are keen to surface these light bulbs so they can support them and increase their scope of impact. In some cases other teachers or schools may benefit from these small-scale brainstorms when they are applied to the big picture.

The challenge with this approach is doing it in a way that is not cumbersome and does not just add another task onto already-stretched teachers. For school leaders, it’s not so much about prescribing any particular innovation, but rather providing a space and opportunity for teachers to share ideas and develop them.

In looking at leaders spearheading innovation, Harvard Business Professor Linda A. Hill has noted that while “all were visionaries capable of creating a vision and inspiring others to pursue it, none considered this their primary role. Instead, they saw themselves as ‘social architects’, whose role was to shape the context. They created communities in which others were willing and able to innovate.”

So how are school systems providing this space for teachers? In all sorts of ways. Here’s how two of them are spurring teacher innovation through new policies and programs, which may serve as a roadmap for others.

Partnering in Georgia

In the case of Georgia’s Gwinnett County Public Schools, school leaders began by bringing in an external group to help the district build a mechanism to surface and develop their teachers’ ideas. The district just wrapped up their first year of a partnership with The Teachers Guild, which is a non-profit initiative of PLUSSED at Riverdale Country School and IDEO’s Design for Learning Studio.

Babak Mostaghimi, the executive director of innovation and program improvement, gathered a team to help answer a central question: How, in a district of 12,000 teachers, could they tap into these minds and empower teacher voice to fundamentally redesign student learning experiences?

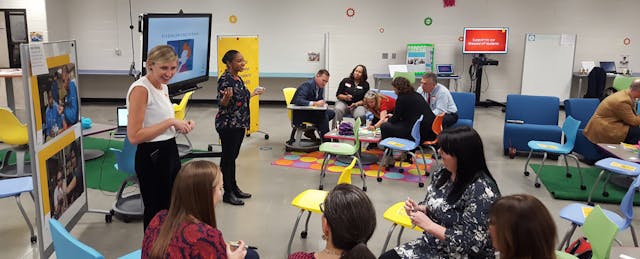

Gwinnett was one of four districts to form a chapter with The Teachers Guild. This year, they started with two middle schools that fed into two high schools and intentionally chose schools that were representative of the county’s student population. Each school had design team leaders selected by principals who expressed interest in the process. These leaders received training directly from the Guild around the design thinking process and brought back this information to their schools.

School design teams started off throwing out ideas, and encouraged teachers to contribute. These 300 ideas were then narrowed down to 65, which were posted on the Teachers Guild’s online platform. This got further whittled down to 12 that showed an initial prototype and nine ideas were presented at an end-of-year showcase. “All of the ideas really evolved because of teachers taking charge, letting their ideas blossom and not saying no,” Mostaghimi said.

As teams dove into ideas, they quickly realized that something that sounded interesting on paper did not always play out the way it was intended during the testing phase. “We were pulling in ideas from teachers and having a rigorous process where teachers were vetting their ideas,” Mostaghimi explains. “Teachers naturally moved away from ideas that weren’t working.” No one from The Guild told teachers whether ideas were good or bad. Rather, Mostaghimi says teachers learned to cast a critical eye toward which pilots were working and which weren’t. “If something wasn’t working, we would think about why it wasn’t working to see how the idea could be made better.”

The ideas that made it to the final presentation were a diverse bunch. One group looked at leveraging virtual reality so students could go on virtual field trips to faraway places like the pyramids of Egypt or the Taj Mahal or see a beating heart from multiple perspective. Other groups looked at flexible scheduling and saw noticeable increases in student confidence in learning independently on a digital platform. Another team realized that, based on surveys, middle school students were not fully informed of the various programs and pathways offered to them in high school—and so piloted a program to build awareness. Some of these will continue to be prototyped while others are fully baked and slated for implementation.

Mostaghimi found that a big takeaway for the teams was the realization that most of the ideas required little to no funding. Of the final nine ideas, only two used extra funds. He also noted that it was great to see the increase in teacher engagement regardless of experience level. Veterans were re-energized through this process and less experienced teachers were given a leadership opportunity. The collaborative nature of the program also meant that while an idea that was proposed by one school may not have fit their context, it may get picked up by another school in Gwinnett County or the larger Teachers Guild community.

“Teachers led the process and put everything together. They led conversations with administrators in their own schools,” Mostaghimi said of the process. “We don’t need every single person to do this kind of work, but we do have a lot of people with lots of great ideas.”

Creating KIPPovators in Los Angeles

Charter school network KIPP LA Public Schools developed the KIPPovate mini-grant challenge to foster innovation by surfacing great ideas from their teachers. Teachers submit a brief interest form, which gets reviewed by a committee. A few are selected to submit a more detailed application to detail out budget, specific goals and the anticipated impact. Ideas have to be sponsored by the school leadership team. A committee composed of members of the KIPP LA School Success Team looks to make sure that the idea is innovative in the sense that it is a new idea and that it is scalable to impact a wide swath of students or teachers.

Selected teachers are invited to a pilot phase in which they receive up to $1,000 funding toward piloting their idea. As a follow up, these KIPPovators meet one-on-one with members of the innovation team every month or two to share successes and collaborate on overcoming roadblocks. Matthew Peskay, chief of innovation and technology, says that this in-person collaboration piece is critical because having people on the ground working with the teachers and really understanding the pilots allows them to get more targeted support.

At the end of the pilot, the teachers submit a reflection to share lessons learned and successes, which the KIPPovate team hopes to use to identify trends on successful projects. If a KIPPovator meets all expectations but the idea just did not work, they receive $500 in recognition for completing the pilot. If the pilot does have a strong impact, the idea is moved to the Accelerate stage where the school receives an additional $2,500 to spread the idea.

In the last five years, there have been 21 pilots ranging from robotics programs to flexible learning environments to a take-home library program, with an even split between those that are tech-driven and not.

Seventh-grade science teacher Kelly West ran a stop motion film festival using Chromebooks and found a lot of value in the program. “It shows that KIPP has an understanding that teachers are coming with different strengths, different experiences, and different passions they can share with students,” she says.

Peskay points to the proliferation of ideas at schools as the program’s success. One pilot centered around robotics has expanded to the point that a schoolwide competition is held twice a year and has become a major part of the culture of the school. He also points to smaller details like noticing the use of stability balls in nearly all classrooms after a teacher introduced them through a pilot.

Yet the program has gone through some iterations. They tried doing half-year cycles instead of a full-year pilot but Peskay advises schools to consider the longer schedule. “The pilot is not necessarily the teacher’s No. 1 priority because they have a lot on their plate,” he said. “To expect trustworthy outcomes in a short amount of time is a bad way to go forward. You’re looking for truthful data, not necessarily success.”