Ariana Garcia doesn’t take a break as she goes from tutoring a small group of students to teaching a social studies class at the Great Oak Charter middle school in New York City.

“Next year, I just want to teach,” Garcia exasperatedly tells EdSurge.

Garcia is one of ten graduate students working to complete New York University’s new Embedded Master of Arts in Teaching (EMAT) residency program. The program, founded by NYU Steinhardt professors, trains aspiring educators by placing them in K-12 schools as they take graduate coursework.

While in schools, graduates slowly go from observing a K-12 teacher in a class to taking over that class as the primary teacher. Professors from NYU (also called content mentors) view this transition via a video platform created by HotChalk and digitally mentor their 15 graduates (also known as interns) for 12 months.

The yearlong credential program comes with a hefty workload and set of expectations. Including Garcia’s agreement with Great Oaks, she juggles about three different, demanding obligations. She works as a school tutor through AmeriCorps, which pays her a volunteer stipend of $12,500 for the year. She also teaches full time at Great Oaks, a gig that provides her with housing. Then at night, Garcia is a student herself, attending synchronous and asynchronous graduate school courses online.

“I feel like I am working really hard and doing things I want to do, but it is really challenging,” says Garcia. “I am not going to take any classes next year, just teaching is hard enough.”

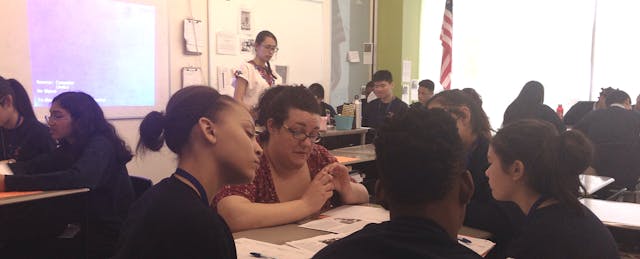

But in the classroom, Garcia’s training is apparent. She repeats student’s answers so they are sure they are heard, her shoulders are up, and she walks around the classroom regularly, with confidence. Garcia does have support when things do get rowdy, though. Under the residency program, participants work alongside a full-time licensed teacher in the classroom. That teacher helps her by walking around the classroom, addressing questions and behavioral issues.

But today is a little different as Garcia is also supported by her professor Dr. Diana Turk. “A lot of you all have been wondering who my professor is, and this is Diana,” says Garcia, introducing her eighth-grade social studies students to her content mentor. This was one of the few times the students interacted with Turk, but they knew she had been watching them through video recordings all school year.

Turk has 15 students in different districts and states. She uses the video system to offer comments and feedback to students regularly since she cannot meet them all in person. Garcia is in charge of recording the class and uploading it to the HotChalk platform, where she tags the video to alert viewers to specific subjects she is addressing in the classroom, and Turk often responds to those tags. Once a week, Turk does a live video discussion with all her interns on the platform.

“Using technology we are offering coursework in an online format,” says Turk “I can have an intern in Wilmington, Delaware, but I am in NYU.” She also tries to connect what she does in her virtual classroom with what the interns are doing in their in-person classes.

“The traditional way university’s prepared students was by forefronting theory, then sending students in the last semester to teach. We reject this and are working to marry the best of the university-based preparation with residency where the interns are embedded in schools,” explains Turk.

Turk emphasized the need to establish clear roles for the students with the schools they work in. She spends a lot of time organizing with funders, school districts, and individuals schools to make the program a run smoothly, particularly since this is its first year in operation. “We are partnering with districts and charter networks. Because we want the partnerships to be deep and sustained,” Turk continues.

She also notes that because of vast differences that exist among districts, the roles of interns within the schools often look different. For example, interns participating in a new chapter of the program opening next year in Syracuse may not have to tutor for monetary support. Instead, the partner district is positioning the residents as teaching assistants in the district, providing them with a $23,000 salary.

NYU plans to expand the program during the 2017-18 school year to San Francisco Unified School District, Syracuse City District, City School District of Albany and Tucson Unified School District. They anticipate about 75 interns that year, a big jump from the original 10-person cohort. “I don’t want the program to get too big because I think what makes its effective is how tightly knit the interns are,” Turk explains, noting that officials plan to grow the program to 120 interns by the 2018-19 school year.

Michael McGregor, the Chief Operating Officer at Great Oaks Charter Schools, is happy about the expansion, hoping that this connection can provide the network with skilled teachers. “We want good people here, we want to have this pipeline,” says McGregor. “It was sort of like a no- brainer for us, let’s get some folks who know how to educate people who want to be educators and make use of that.”