Editor's Note: As we scramble to adjust or contest changes to education on a daily basis, it's hard to keep focus on the "big picture." Here's one snapshot of what the future of learning could look like, circa 2025. Share your projections on the future of learning below.

“Education is a social process; education is growth; education is not preparation for life but is life itself.”—John Dewey

Jason journeyed down into the canyon once again. His dam stood still unfinished, and the rainy season (insofar as that existed in Southern California) would soon begin. Scurrying around the stream, he wedged pebbles and a slice of PVC pipe between the four small boulders he had carefully placed the day before.

A small voice piped up helpfully. “Quite the structure you got there—reminds me of the great Roman dam of Cornalvo.”

“Quiet, Tock, I’m not done yet.”

Jason fiddled with the pipe and some mesh screen to create a coarse water filter. As he fitted the pipe in place into the pebbles, a small hole opened up in the lower right part of the dam, as the increased pressure pushed the sand and dirt filling through the rock superstructure.

“Ok, Tock, tell me about your Roman thing.”

“Jason, the Cornalvo dam was built during Rome’s Augustan age, in the first or second century AD. Located in what is now the Spanish province of Extremadura, the earth and stone dam still stands largely...”

“Built from little more than dirt and still intact...That’s pretty impressive, Tock.”

As he talked, Jason stared at the water flowing through the hole and his now mostly useless pipe. He tried shoving sand into the hole, but the pressure gradient became too large with the filter in place and soon enough the hole would open up again.

“Tock, I don’t have time now but this afternoon after seminar let’s block in a unit on Roman architecture. I’ll start with a quick video overview of that time period and then maybe dive into some firsthand accounts, insofar as they’re available. Need to figure out those dudes’ secret!”

“Sure thing, Jason. Also, remember, we need to be at seminar in fifteen minutes.”

“Ya, you’re right. Tock, before we go up, can you pull up that schematic I did yesterday again?”

“Here you go, Jason.”

“Hmmm, how might we build out the base so it can handle more pressure? Let’s take a picture of the dam as is and head up.”

Jason climbed up the canyon into a rounded amphitheater, eagerly showing the picture of his failed dam to the guide who was lingering by the opening of the circular seating.

“Cool design. You’re right—pressure’s the key issue. Here, after seminar, let’s discuss how you might integrate some trigonometric concepts into that design to solve your base load problem.”

“Trigi-what now, Mr. Henderson?”

The guide smiled. “Don’t worry, nothing more than applied geometry in this case. You’ll work it into your dam and grok it soon enough.” He turned to address the assembled twelve person group. “So what cool frontiers did you explore today?”

“I did a virtual walking tour of Seoul on my Tock 5000.”

“We played with robotic arms!”

“I interviewed a JPL scientist about current developments in interstellar travel.”

“Alright, everyone, get out your Tock. In that inquiry, what learning barriers did you encounter? How did you overcome them? And, most importantly, what learning did you bring back to advance our group’s focus theme of ‘the role of technology in human progress’? Take a few minutes to collect and write down your thoughts.”

As Mr. Henderson talked, Jason’s father sat down in the back row of the amphitheater, laughing to himself as he remembered how differently people approached learning just a generation earlier. Back then, a kid like Jason could just as easily play with dams or browse digital knowledge on Roman history, but the virtual infrastructure that would up becoming the backbone inquiry-led ecosystem barely existed.

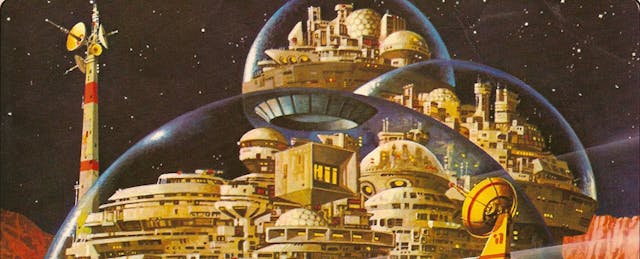

Jason's father knew that after the seminar, Jason would go on a "linked-learning matching platform," and find a local engineer named Vivek with expertise in earthen dams that he could ask targeted questions about his problem. Jason would follow Vivek around in a job shadow to see how the engineer approached dam construction. And in a few weeks, Jason would tag along with Vivek at an industry retreat in Yosemite where Jason would see the state of the art in infrastructure management and hear blue-sky dreaming about how humanity might terraform Mars to make water flow over its surface once again. A month later, he would apply for an internship at that local firm where he might continue his development under Vivek’s tutelage and pursue his dream of colonizing Mars.

How Schools Began Sharing 'Tribal Knowledge'

The kinds of viral interactions which became the lifeblood of Jason's education were once left to little more than chance—at best, a connection through a noble but understaffed nonprofit but more likely a serendipitous meeting in the community. Rigid instructional mechanisms like lecture-oriented classrooms, age-driven grade levels, and standardized testing fostered a learning culture oriented toward following preset rules, going at one pace and figuring out how to check the right boxes.

Over time, however, community members demanded a move away from formulaic thinking, recognizing that the world lacks a back-of-the-book key where a student might find the one correct answer. Firefighters, doctors, small business owners, nurses and other local professionals took on a more pro-active role in sharing their "tribal knowledge" with students. Members of the community came to expect that they both shared their intellectual pursuits across generations and that everyone engaged in lifelong learning.

Rather than getting bogged down in arbitrary distinctions between “academic” and “trade” learning, the community recognized the value of going both up and down the ladder of abstraction. They found unity in focusing on the deeper issue of releasing human potential. The emphasis on "meeting standards" began to fade, replaced instead with the idea of "developing purpose," or finding deep meaning in an individual life and in the value that a student seeks to add to our broader human civilization. Multiple choice testing gave way to asking students to build a portfolio of their work.[1]

Rigor was created through peer evaluation, self-generated goals and open-ended knowledge assessments. The most pivotal projects were judged by panels of community members. And rather than thinking through the lens of school choice, the community worked to build a level playing field by creating an inquiry-based education ecosystem where all individuals had the freedom to reach their potential. This conceptual framework would hold water just as well in Plato’s school well over two millennia ago as today in the twenty-first century.[2]

Perhaps the best exemplar of the principles behind the new education system became a program called "thinkquest"—the culminating project for all students' basic education (what was once called high school). Thinkquest was designed as a two-year, open-ended inquiry that forced students to set a big goal, develop a plan, hold themselves accountable, and adapt to changes in their path as needed.

The only requirement is that thinkquesters pitch their ideas to a panel of community judges who examine how much value the project could add to human civilization. Although projects occasionally fall under familiar categories (like scientific research, public service, or business development) they more typically cut across such areas. Students may fail to achieve their ambitious goals—or even struggle on incremental steps such as Jason did when working on the filter for his dam. But that reality does not induce shame. Rather the community works to encourage individuals to embrace failure and turn it into motivation for future individual growth.

How Far Away is This, Really?

In 2013, an education like Jason’s seemed fanciful—almost science fiction. But many of the foundations for what could become this sort of inquiry-driven ecosystem (our fanciful friend, the TOCK 5000, included)were already in existence.

Platforms such as Quora offered a virtual glimpse into how community might transform education. The nascent collaborative consumptive economy hinted at the increased ease in which community might be activated. The popularity of meetups and skillshares suggested a hunger for local knowledge and desire for lifelong learning across diverse groups.

Looking at what might classically have been education technology, the explosive growth of Khan Academy or MOOCs demonstrated the ubiquity of accessible knowledge and hinted at the immense opportunities when easy access to well-developed curriculum became a given. At a deep level, the foundational ingredients of an inquiry-led ecosystem—connectivity, information abundance, and design iteration—-already existed in exemplars like the iPhone, Wikipedia, and Y-Combinator.[3]

Still the key shift came not through technological development but through a broader cultural awareness and development of new structures to build an institutional platform around the new tools—pivotally, when local communities organically began to develop their own centers of excellence for community education.

These initiatives allowed for localized design, development and testing new learning models to take advantage of the new learning reality. Recognizing that individual humans have their own unique patterns and predilections, such centers provided the space for the culture of experimentation needed to build today’s inquiry-based education ecosystem. These avenues for exploration satiated a hunger for challenge and discovery that the historical legalistic risk aversion had all but stamped out (see for instance the stifling of playgrounds or media-induced fear of strangers).

Such organic, community-driven structures transcended the opportunity gap, providing the impetus for the one-on-one human interactions that broke down tribal divisions. No longer hidden by bureaucratic structures, the quintessentially human ability to connect through the sharing of information became the dominant logic of the new system.

Who wouldn’t answer a question on the new online forums simply because the inquiry came from a different zip code or the questioner had a different shade of pigmentation or some other arbitrary distinction? Such tribal considerations came to be seen as beyond petty, and the norm grew towards satisfying the universal human drive for curiosity as the primary goal.

Unleashing Human Potential

In retrospect, many of these changes seem almost obvious. In a world that's changing so rapidly, why wouldn’t you build our education system around what we don't know rather than around what we do? Recognizing that learning can happen anywhere, why wouldn’t you structure an education ecosystem that goes beyond the walls of a classroom or a school site? Looking beyond somewhat antiquated distinctions like grade level or student status, why wouldn’t you develop pathways for linking inspiration to inquiry for all humans in our civilization?

Still reminiscing at the back of the amphitheater, Jason’s dad felt blessed to have had parents who raised him in a wonderful community that already provided these sorts of little opportunities that made learning—and really life—magical. Looking at his son passionately explain his dam design, he felt a deep pride not only in Jason but in the progress of a culture that made such experiences commonplace. And who knew? Maybe, in the future, Jason would indeed go on to pioneer the first dam on the red planet.

Notes:

1. See for instance the discussion on Prussian forestry management in Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott and witness the same issues with legibility in Prussian style public education—interesting to muse on the continued influence of centuries old Prussian management practices on today’s society! Also for a more context-specific history, please see the Education and the Cult of Efficiency, which offers a tremendous analysis of the obsession with scientific management practices in education a century ago. Or please see Sir Ken Robinson’s famous TED talk on Changing Education Paradigms.

2. For some deeper thinking on what I’m driving towards with these concepts, please see Terrance Tao’s comments on mathematical maturity, Keith Devlin’s articulation of R. L. Moore’s “Discovery Learning” method, Lockhart’s (in)famous lament, or the Norton Juster’s indispensable The Phantom Tollbooth (who serves as the inspiration for our hero’s good friend Tock).

3. For a much better overview of this space, please see for instance Salman Khan’s One World Schoolhouse or New Schools Venture Fund’s map of the education technology landscape. Notably, many of the most inspiring and engaging parts of Salman Khan’s book have little to do with his famed videos but rather what’s possible when you go beyond curriculum.