That the top 400 performers in Sebastian Thrun's 160K-student Artificial Intelligence course didn't include any Stanford students wasn't the only major Udacity revelation on Monday. While Thrun joined Sal Khan and Joel Klein for a panel discussion at TechCrunch Disrupt, Daniel Collins of AngryMath blog fame was busy revealing his own 10-point review of Udacity's Statistics 101 MOOC.

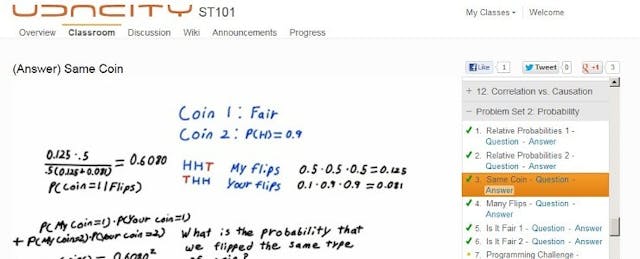

Collins' review touches on several substantive issues -- chief among them being the loose handling of well-defined stats terminology like population and sample. As Collins writes, "the very word 'statistics' means measures for one (sample) and not the other (population) -- but you'll never learn that from this class." Among other statistics no-nos, Collins bemoans the lack of any normal curve calculations and observes that the Central Limit Theorem is "never clearly stated."

Beyond these conceptual mishaps, the remaining issues might just as easily be found in a thorough student course evaluation -- in other words, they're issues shared by any course, online or not. This doesn't devalue Collins' perspective -- he holds an M.A. in Mathematics and has taught introductory and intermediate math and computer science courses at the college level for over five years. It's safe to conclude that he's as qualified as anyone at introducing new statistics concepts to learners. But it's important to discern between quality of content, and the pedagogical issues that plague all types of learning environments.

When contacted by EdSurge, Thrun offered up a swift and thoughtful response both to us and on his blog. "What our course does well is driving intuition and focusing on student exercise. But the writer is correct that there are inconsistencies that need to be fixed - and we will fix them. And we will add some of the material he suggests," he wrote.

Among the toughest charges leveled at Udacity was that the professors aren't “listening” to students and so aren't getting enough feedback to fine-tune the program. Thrun says that's just not true. The teachers "spent a ton of time on the discussion forums and a lot of clarifications and corrections are posted and discussed there," notes Thrun.

It's too early to judge how Udacity might award "credit" for work, Thrun says. He writes: "We specifically don't think of the online classes as a way to drive genuine certification. The fact that our exams can be taken multiple times is to make sure students can practice until they get it right. We should articulate this more clearly at Udacity."

The difference, at least one Udacity student noted, is between a one-time "test" score and having a chance to build a sense of mastery. Collins "...doesn't understand the rationale behind the fact that it's possible to pass several time the last exam. It's really great because it allows 1) people to be relaxed when they pass the exam 2) compensate the lack of exercises and interaction with the teacher 3) and the most important is that it allows student to work until mastering. When they miss something, they can go back to the part of the lessons they did not understand and take the exam again," writes a commentator on Udacity's blog.

The AngryMath blogger contends that the MOOC industry "will turn out to be an over-inflating bubble that bursts at some point, much like other Internet sensations of the recent past." We doubt it. Instead, we're guessing that MOOCs will become a part of the education landscape just like, oh say, bloggers have become a fixture on the journalistic landscape.

Building online curriculum should involve "a dialog with the entire industry," Thrun writes. "I am proud of the stats class but there are many ways to improve it." To us, that means thoughtful criticisms and constructive dialogue more so than parodied YouTube videos.