The FDA’s decision came on Monday: It would authorize emergency use of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in 12- to 15-year-olds. Two days later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention followed suit, recommending that adolescents—the youngest population yet—begin receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.

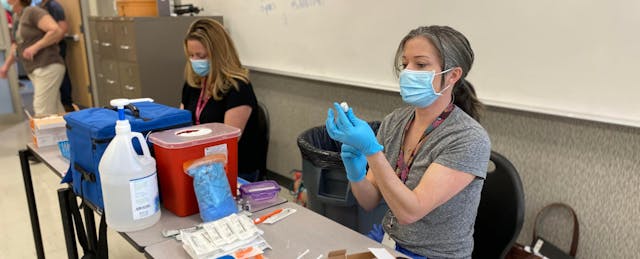

By Thursday morning, less than 24 hours after the CDC’s endorsement, the nurses at Mt. Lebanon School District were inoculating middle schoolers, watching them wriggle with anticipation, calming them as they winced at the needles and then celebrating the momentous occasion with them.

At the day’s end—in five hours, to be precise—about 10 nurses had helped administer nearly 1,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine to students, averaging about four kids a minute. They had perfected the process, problem-solving every hiccup, after months of practice administering the vaccine to adults in the community, including school staff. It’s what allowed them to turn the vaccine clinic around so quickly after the CDC’s announcement. (Well, that and their newfound ability to transition from in-person to remote learning at a moment’s notice.)

“The kids were ecstatic,” says Deanna Hess, chairman of health services at the Pittsburgh-area school district. “They’re just so excited to get back to that normalcy—whatever normalcy is for them.”

School nurses have played an integral role throughout the pandemic. In many districts, they have stepped up over the last 14 months to provide COVID-19 tests, conduct contact tracing, set protocols for quarantines and serve as the liaison between schools districts and public health departments.

Now, as the U.S. rounds the corner on this crisis, their responsibilities have expanded. Many school nurses are putting shots into the arms of children as young as 12 and acting as trusted confidantes and guides to families who are not yet convinced vaccination is the right choice for their children right now.

“In order for students and parents to feel safe returning to school, vaccination is the key,” says Kate King, director of health, family and community services for Columbus City Schools in Ohio. “The more people are vaccinated, the safer everyone is going to feel coming back to school. And we need children back in school.”

Excitement and Hesitation

In the first six days after eligibility was expanded, the U.S. vaccinated about 600,000 children between ages 12 and 15, according to the CDC. A total of 3.5 million children under age 18 have now received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

At a drive-through vaccination site in El Paso, Texas, last weekend, hundreds of kids showed up with their parents to get the shot. Rebecca Madrid, a nurse manager at the nearby Socorro Independent School District, describes the scene as pure excitement.

“You would see on the parents—just relief,” Madrid says. “You would hear the ‘thank yous.’ Once they got the vaccine, you could see the smiles on their faces.”

Rebecca Doughty, director of health services at Spokane Public Schools in Washington, said students and parents alike have come to their clinics buzzing with excitement in the last few days.

“The kids want to get back to normal life,” she says. “They’re nervous about the shot itself—they’re still kids, after all—but they are excited to have the vaccine. They know that’s how they’re going to be able to have fun this summer.”

But now that the most eager families have had the chance to get vaccinated, and get their eligible children vaccinated, the hard part begins.

While many families of school-aged children are desperate to get vaccinated, others have no interest at all. And then there are those who are on the fence, unsure of how to weigh the risks and benefits or what to make of all the conflicting information they are hearing about the vaccines.

Doughty says she has personally encountered a lot more parents who are “vaccine-absolutely nots” than those who are vaccine-hesitant.

“There’s quite a bit of paranoia,” she explains, mostly stemming from misinformation circulating online.

“I’m a bit constrained by wanting all of our students to feel welcome in our school district, but also wanting them to all be vaccinated. It’s a bit of a tightrope,” Doughty says.

School nurses—especially those who have worked in the same community for years or even decades—have the advantage of being a trusted health care provider to many families, says Laurie Combe, president of the National Association of School Nurses.

What school nurses can do—and what thousands all across the country have been doing for months—is take the time to speak with parents and to really listen to them. Why are they hesitant? What is it that is holding them back? Is there research available that might dispel their fears?

“School nurses are not saying, ‘You should do this because this is what the data says,’” Combe explains. “What school nurses are doing is saying, ‘I really understand this is your concern. This is what the evidence says related to that concern.’ So it’s meeting parents right where they are, trying to give them the answers and evidence they can consider.”

One critical barrier, says Lisa Kern, a school nurse at Pasco County Schools in Florida, is getting the parents to embrace the vaccine for themselves. If they aren’t comfortable getting it, they are unlikely to want it for their children, she says.

“It’s all about education when it comes to vaccine hesitancy,” Kern says. “There’s lots of misinformation out there, so any opportunity we have to correct the narrative, we have to take those opportunities.”

Listening to parents’ concerns, understanding their fears, acknowledging their hesitations, “that’s definitely a school nurse’s wheelhouse,” Kern says. “It takes time to do that. It’s not a quick conversation you have with folks. You have to answer their questions. You can’t be judgmental.”

Everyone needs to have a reason to get vaccinated, Kern adds. The reasons may be different for each family. Maybe someone’s grandma has a 90th birthday coming up. Or another family wants to go on vacation. Or they want their child to get back to playing team sports. It’s important to help families identify their reason for getting vaccinated so that they can see what good may come of it.

Racing Toward the End of the School Year

Another reason that districts like Mt. Lebanon and Spokane have hustled to set up vaccination clinics for 12- to 15-year-olds? The school year is quickly coming to an end.

Since the only vaccine currently available to adolescents is Pfizer’s two-dose option, school nurses know they are racing against the clock to get as many kids inoculated—with both doses—before school lets out for the summer.

Take Mt. Lebanon, the district that opened a clinic and vaccinated almost 1,000 students following the CDC’s announcement. Those students were inoculated on May 13. Three weeks later, on June 3, they will get their second dose. The next day is their last day of school.

For other districts, the timing will not be as fortuitous. In Columbus, Ohio, staff are still vaccinating 16- to 18-year-olds and will begin focusing on younger students this summer. They will inoculate 12- to 15-year-olds through summer school programs, which begin in mid-June, and at summer food sites where students come to pick up nutritious snacks.

Kern’s district near Tampa, Fla., wraps up classes next week. “There’s definitely no time” to start vaccinating the younger groups before then, she says. And besides, in Florida, a parent must be present for their child to be given a COVID-19 vaccine, since it does not yet have full FDA approval. Instead, Kern’s district will host weekend and summer vaccination clinics.

The goal, ultimately, is to get as many kids as possible vaccinated by the end of the summer. That way, when schools reopen in the fall, the need for contact tracing and quarantining will be limited, and the disruption caused by COVID-19 will, with any luck, be minimal.