I’ve always been fascinated by watching the movement of ships. It probably comes being part of a Navy family, but seeing massive floating vessels of steel gingerly navigate through locks, canals and beside intricate docks reminds me of the power of carefully steering organizations.

Just as changing the direction of a ship requires a series of small, calculated movements, undertaken over a period of time, so is the work of transforming the instructional practices of a large, complex school district. Quick spins of the wheel are the equivalent to flash-in-the-pan initiatives that result in haphazard decision-making, new idea fatigue and educator overwhelm. Long-term effectiveness is born from many small nudges in a consistent direction, never losing sight of the goal on the horizon.

My school district, Frederick County Public Schools (FCPS) in Maryland, has undertaken a careful, strategic turn towards Mind Brain Education (MBE)—the intersection of research in the areas of education, neuroscience and psychology—with a goal of ensuring that every educator understands how the brain learns, works, grows and thrives in order to improve outcomes for every learner.

Our district serves 44,000 students and employs more than 6,000 staff who share many of the same concerns as our colleagues across the country: our schools range in size, our communities are diverse and rapidly changing and our students face challenges of poverty, trauma and language acquisition.

Teachers and leaders in our district strive to create the best conditions possible for learning while juggling increasing demands and limited resources. In 2019, twenty-five years after joining FCPS as a teacher, and experiencing a variety of roles, I stepped into a position leading the department of organizational development. Our team is tasked with providing professional learning and leadership development through the lens of research-informed practices. Steering a ship as big as ours requires careful and strategic nudges that lead to innovation and growth.

From the start, we knew we’d need an area of focus—and to get buy-in, it had to build upon prior work to move the needle further. We decided to build our work on a solid foundation that started in 2012, when we created a school culture framework around mindsets. With a thorough understanding of both the power and the limitations of the research around mindsets, we determined that MBE was a through line to our three systemic priorities—a focus on equity, high quality instruction and a collaborative process to monitor student progress. MBE could also be used as an anchor in discussing instruction, assessment, equity, social emotional learning, teacher evaluation and more. Ultimately, we prioritized ensuring that every FCPS educator understands how the brain learns.

Figuring out how to leverage MBE research to transform the instructional practices of such a large school district took time. One thing we recognized right away was that we couldn’t make MBE an initiative—no quick spins of the wheel, no year-of-the-brain posters, no jazzy guest speakers. Making MBE an initiative would run the risk of our teachers and principals perceiving the work as one more thing on their already heavy plate.

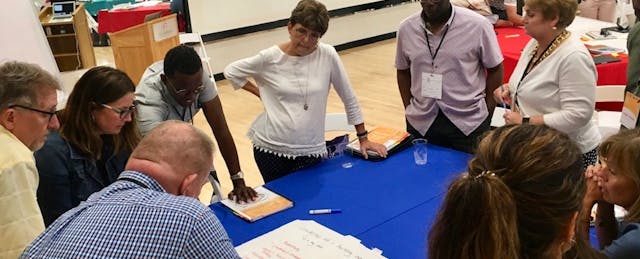

Like many large school systems, FCPS is fortunate to have a dynamic and committed group of teacher specialists. These educators work directly with teachers and administrators, serving as mentors, curriculum writers, and professional learning facilitators for our workforce. We began our intensive MBE learning with this group, recognizing that their influence would catalyze the work organically.

We framed our work around four questions, through the lens of research:

- What should we keep doing? There are many research-informed strategies to improve instruction and support student wellbeing that are rooted in truths that my colleagues and I saw daily in our own classrooms. Even though we don’t always have the knowledge of brain science or the academic research that proves why a strategy—like having students quiz themselves using flashcards—is effective, our experiences in the classroom provide us with evidence that it is. Affirming strategies that people are already comfortable using reinforces their professionalism and expertise.

- What should we retire? This question is anchored in a quote from Dr. Maya Angelou: “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” Advances in our understanding of how the brain best learns have grown by leaps and bounds over the last two decades. Some of what we thought was good practice years ago, like giving students learning style inventories, is no longer supported by research. That doesn’t mean that it was wrong then, but it is wrong to continue doing now. We put those strategies on the “retire” pile.

- What do we revise? The heart of this work lies in wrestling with the nuances of what works under which conditions and making appropriate adjustments. This is where the dynamic creativity of our teachers makes a difference. Take, for instance, the flashcards example. Maybe we’ve been suggesting that students quiz themselves using cards. But have we taught them why or how? Have we shared with them the importance of pausing to retrieve the information before flipping the card over? If not, we need to tweak our practices. There are many cases in which we make subtle changes to our strategy or curriculum based on MBE research to improve teaching and learning.

- What do we need to start doing? Sometimes it's tough to figure out what's missing, but considering new ideas and practices that might support student learning is critical. Our work in the area of equity and growth mindset, for example, helped us unpack our thinking about student achievement, purposeful work and expectations, but until we learned about the research around the mindset of belonging, we were missing a critical component of the equation. By actively focusing on developing a sense of belonging in our schools and classrooms, our students were better able to spend their cognitive energy on learning, rather than wondering, “Do I really belong here?”

These four questions helped us categorize our instructional practices so we could determine where we need to continue, stop or change. So far, starting the learning with our teacher specialists has yielded exciting results. Our math curriculum now includes spaced practice at all grade levels. Our English language learners now benefit from retrieval grids as they work to become proficient in a new language. Our primary teachers are talking about cognitive load—or the mental effort associated with tasks—and how designing lessons that recognize its importance, help our littlest learners to fend off frustration and overwhelm.

While we gradually help our teachers understand its importance, we know that our students are already benefiting from the use of MBE built in to the curriculum design and materials. That’s why our courses for new teachers reflect our system’s value that each teacher should understand how the brain learns.

This work, and the changes we’ve made as a result, would be impossible without support from our district’s senior leaders and our Board of Education. In summer 2019, members of our leadership team attended the Science of Teaching and School Leadership Academy, a week-long event with in-depth learning about MBE .

That investment led to integrated approaches, curriculum enhancements, conversations about technology use and discussions about how to balance joy and rigor in administrative professional learning. Three Board of Education members recently attended an MBE training alongside our teacher specialists to learn about specific MBE research and its connection to learning and wellbeing. When designing and facilitating professional learning experiences for teachers and administrators, our superintendent and deputy superintendent use and highlight MBE strategies. Recent sessions used retrieval to ensure that content shared last month wasn’t forgotten. These leaders don’t pay lip service to the work, they embody it. And they strive to be research-informed educators, too.

As we steer our ship toward ensuring that every educator in our school system understands how the brain best learns, we’re making many collaborative, strategic changes all moving in the same direction. We know that the success of strategies is contingent upon their use in context, meaning daily application in the diverse classrooms across our district.

We recognize the link between emotion and cognition. Research will guide our work with learners, both children and adults. Our ship has sailed and we’re committed to keep learning.

| Interested in learning more about MBE? Here’s a recommended reading list with some favorites of FCPS staff: |

| * “Neuroteach” by Glenn Whitman and Ian Kelleher * “Mindsets in the Classroom and Create a Growth Mindset School” by Mary Cay Ricci * “Powerful Teaching” by Pooja Agarwal and Patrice Bain * “Ingredients for Great Teaching” by Pedro de Bruyckere * “The Knowledge Gap” by Natalie Wexler * “The ResearchED Guide to Education Myths” Edited by Craig Barton * “The Science of Learning: 77 Studies That Every Teacher Needs to Know” by Bradley Busch and Edward Watson |