When Suparna Chatterjee was taking a graduate online course at New Mexico State University two years ago, she had to complete an ice-breaker activity where she was asked to create her own superhero.

But Chatterjee, an international student from India, did not feel confident about the assignment, and thought it was Western-centric and focused on physical powers associated with attractive males.

Based on that feedback, the professor, Julia Parra, says she changed the assignment to make it broader, and more inclusive. Instead of just superheroes, she invites students to think about their own cultural icons and cultural representations, and use that to design a character.

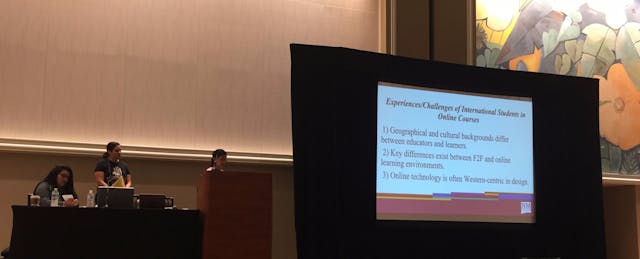

The student and professor both shared the story last week during a session on culturally-responsive teaching in online courses at the 2017 OLC Accelerate Conference, in Orlando.

Another panelist, Nouf Alsuwaida, an international graduate student at New Mexico State, also stressed that it is important to give students choices in how they perform assignments, noting that some prefer to work in groups while others best thrive solo.

Parra, an assistant professor at New Mexico State’s department of curriculum and instruction learning design & technology, says she’s offered her students the opportunity to use their own languages to complete activities.

“To be honest, I’ve only had one or two students take me up on it,” she said. “Because what they note is, if you’re in a safe environment with a safe class, they would rather use English, because they’re trying to practice their English and become proficient in English.”

Parra also gives her students options for her assignments that go beyond language. For example, she lets students pick if they want to do text-based reflections, or video or audio-based reflections. She also lets them decide if they want to reflect in a discussion forum with their classmates, or personally send her their reflections. “I have students really take all of those choices,” Parra said.

“Group work in face-to-face classes can be challenging as it is,” Parra said. “But bringing it into an online setting adds that extra layer of technology challenge and collaboration-skill challenge.”

Instructors should make sure students have the opportunity to build their own learning experiences, Parra argues. She said that one of the ways she implements active participation is through participatory course design in some of her courses, where students take part in brainstorming what the course will look like. She takes the approach of co-designing.

After Parra has combined her learning goals and objectives with that of her students, she gives it back to them, and asks them for their ideas for the activities and resources that they could do in the course and assessments. In the end she builds the final syllabus based on their suggestions.

Parra admitted that she does a “little bit” of seeding, where she gives the students her ideas of what she thinks might work, and the students often come back with some of her suggestions.

“What then happens is they give me better ideas on actually how to implement—and better ways to actually assess what we decide to do.”