Middle schooler Hannah Levenberg always liked taking things apart, but she didn’t make the connection between her tinkering and technology until she took a class from Mr. Moredock. He taught her how to code in her seventh grade Innovation and Design class at Redwood Day School. The following year, he challenged her to design a unique project using Arduino circuits. Hannah built a Whack-a-Mole game—and learned the invaluable skill of troubleshooting, the importance of asking for help, and just how far persistence, curiosity and creativity can take you.

Hannah’s experience reflects the innovative ways educators across the country are drawing students into the Maker movement. In fablabs and makerspaces, STEAM rooms and classrooms, students of all ages aren’t just tinkering—they’re tackling projects that foster the design thinking and creative problem solving skills they will most certainly need in the future.

With her first big making project almost complete, Hannah shared with EdSurge her favorite troubleshooting technique, advice for other student makers, and why it’s important to “prove what you know.”

EdSurge: How did you become a maker?

Hannah Levenberg:

When I was younger, I used to visit my dad’s office and take apart old broken computers for fun. I had no idea what any of the stuff did, but I was sorting the capacitors and the resisters. And I’ve always had a lot of ideas for projects, like a hoverboard for reading books in the bath. But I never made the connection between those ideas and technology—until my seventh grade tech class.

In most of lower school, I was pretty opposed to making because I didn't really know what it was. But in seventh grade we did coding with my teacher, Mr. Moredock. I remember he showed us a simulation of flocking birds and explained that they were just programmed with a certain set of rules. I thought that was really cool. I got into programming that year and I’m building on that with circuitry this year. Now, I'm learning new things every day.

Can you tell me about your Whack-a-mole project, and how it works?

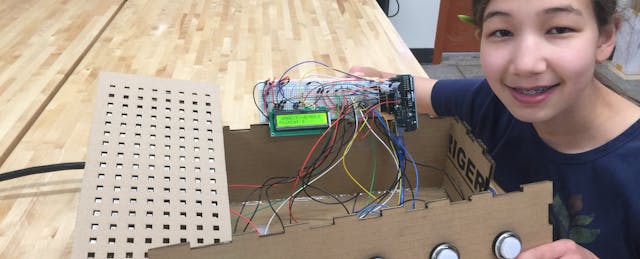

I thought it would just be a small project, but then I got really into it. I’m hoping I’ll be finished before the school year is out. Then I’m going to put it in the makerspace at my school and leave it there after I graduate, so other students can play it and hopefully get inspired by it.

It’s just like the typical game, except instead of a hammer there are different buttons and they light up different colored LEDs. It’s pretty simple; when you hit them they record your score. I programmed it through an Arduino UNO and it’s all hooked up to the circuit board using a large breadboard.

What was the hardest part of making the game, and what did you learn from it?

Writing the first version of the code was easy. It just didn’t work. But I thought of it as a challenge, so I wasn’t too upset. I did it over winter break so I spent about two to three weeks and I had to troubleshoot it over, and over again. I kept finding little wires that weren’t connected just right.

The main troubleshooting technique I’ve learned is to never assume anything is working, or as my father would say, “prove what you know.” When my Whack-a-Mole prototype wasn’t working, I would make a list of things that could be wrong and test them individually. It sounds time-consuming, but is actually quicker than randomly guessing. It was also a lot of fun.

One of the best lessons I’ve learned from Mr. Moredock is that it’s OK to make mistakes. There’s a quote on his wall from James Joyce that sums it up best, “Mistakes are the portals to discovery.”

What was the most fun part, and the most rewarding?

It was the feeling of accomplishment I got after troubleshooting. I’d look at all the little individual pieces—parts that could possibly be a little bit off—and come up with creative solutions. I like problem solving.

Now my game has these large buttons with LEDs in them that light up when you whack a mole, so it's really satisfying. Then there's a little point counter I added after I taught myself how to use a liquid crystal display. That was also fun. Plus, I like that it's something in the real world, something that's usable.

What advice do you have for other student makers?

I'd say don't be afraid to ask for help, because that's something that has held me back.

For example, in one of our tech classes Mr. Moredock was explaining why in a simple circuit, the resistor can be placed on either side of the actuator and it will have the same effect.

It took me a whole week to tell Mr. Moredock I didn't get how this worked—because I was self-conscious. When I finally asked Mr. Moredock, he explained it in another way and I understood. I wish I had just asked right away in class; it would have saved me trouble and I could have helped my classmates understand as well.

Making is a great way to learn about persistence and creativity, which can be helpful in other subjects. You can be frustrated, but then you get a really cool reward if you persist—because there’s an actual thing that you build.

Making can also help you understand a lot of things about the world around you. For instance, I can’t turn on a light switch now without thinking of the potentiometer inside the dimmer. It also makes it really easy to see something that needs improving, or think of a completely new appliance that you could use.

Do you make things outside of school?

Yes, I made these little hand warmers for my mom for her birthday because she's always cold. They're little fabric-wrapped resistor gizmos that you just turn on and off, and they heat up pretty nicely.

And my Dad and I just finished building a chicken coop for a school in Emeryville as part of our 4-H program; it’s taken about two years. We designed the chicken coop, asked businesses for donations, and then we built it. We learned a lot about construction and fundraising and design. And now . . . the students at that school can learn about taking care of animals.

Even though we finished the coop, now now I’m using Tinkercad to model things and learn more about the measurements and the architectural process.

Has making influenced how you think about your future?

I’ve wanted to be a teacher for the past few years, and my tech class and making strengthened that. Now I’m thinking I want to be an educator in the science fields. I picked the high school that I’m going to next year, Lick-Wilmerding in San Francisco, partly because of its science and maker programs.

Also, I still have a lot of ideas, some of which are terrible—but some could be really good! And now, because of my making experience, I feel encouraged to go forward with those projects.

Autodesk's new Maker Starter Kit provides ten steps to help you launch a maker program in your school, organization or community. Access the complete Maker Program Starter Kit here.