The image of screens strapped to students’ faces is what the future of education looks like to some, but others see it as a passing fad that educators will look back on and say, ‘What were they thinking?’

Many proponents of immersive virtual reality in classrooms—using devices like Oculus Rift or Google Cardboard—say one question will be key to the fate of the tech in education: Will these new systems make students and professors content creators, or merely consumers?

A couple of efforts presented at last week’s SXSWedu conference hoped to make it easy to capture and create 360-degree videos or immersive images for educational purposes.

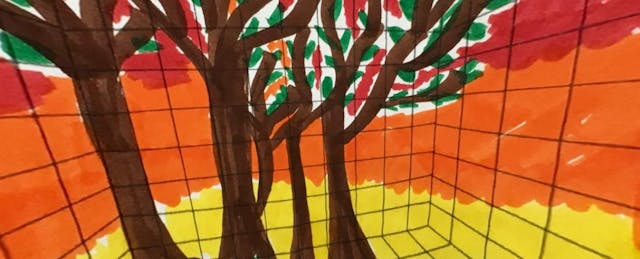

One of these projects relies on decidedly low-tech tools: crayons and paper. The system, called Panoform, requires users to print out a special grid, similar to graph paper, where the lines are curved just right so that the image can later be viewed in 3D. Teachers can hand out these grids, along with crayons or markers, and ask students to draw a design or character to bring into the immersive world. Then the students or instructors take a picture of the paper with their smartphone’s camera and upload the file to a website that converts the image to one that can be viewed with Google Cardboard or a similar device.

The service is free, and it’s the creation of researchers at North Carolina State University’s Immersive Experience Lab. “It’s an easy, cheap way to make content for VR,” says Luis Zapata, a researcher at the lab. “Simple pen and paper is all it really is.” The lab members set up a table to demonstrate the system in the “Playground” area of SXSWedu. True to the space’s name, visitors could grab a colored marker and grid to make their own creation, and you can check out some of the creations on the Panoform website. “We’re trying to get it out to instructors and educators,” says Zapata.

Meanwhile, a few tables over, representatives of Barnard College sat at a table describing their own effort to encourage the creation of VR content. Their idea: The college’s Instructional Media Services department loans out kits to students that include a camera to capture pictures and video in 360 degrees. They also offer training on how to edit the videos and display them on VR systems. “Everyone is trying to figure out what to do with VR, we’re going to have the students try to figure it out, too,” says Abby Lee, an instructional media services assistant for the college. It’s a model that other college libraries and equipment desks often use to try out new technologies.

One student choreographer at Barnard, for instance, filmed a rehearsal of a dance troupe she works with using the 360-degree camera. Once she was able to view the footage through a head-mounted VR rig, she noticed things she hadn’t realized and made changes to her choreography, says Melanie Hibbert, associate director of instructional media services for Barnard.

But will converting images and footage to immersive VR be worth the cost and trouble in the educational setting? After all, there was plenty of buzz a decade ago for teaching in Second Life, a 3D virtual world online. Few educators use it today, and some may not even remember it. Could immersive VR join a long list of overhyped educational technologies?

Derek Ham, an assistant professor of graphic design at NC State who is the principal investigator for the Panoform project, argues that VR will catch on online if students can build worlds, not just watch them. He says that has been the key to success for Minecraft, the 3D environment that allows users to build their own worlds from simple graphical building blocks, Lego-style. The platform has become a cultural phenomenon and is popular with students and educators.

“That’s why Minecraft is working so well today. It’s not just a game,” says Ham. In immersive VR, he adds, “we’re trying to make you a maker of content from day one, rather than just a consumer.” In other words, what VR needs, he says, is a ‘Minecraft effect.’