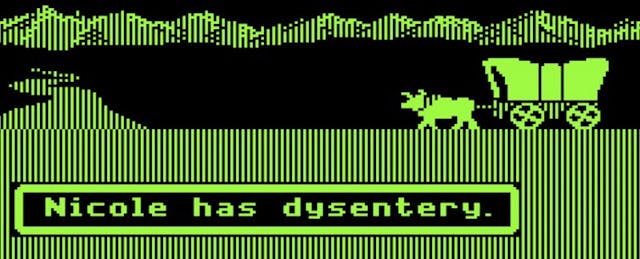

Fifth grade was one of my favorite years in my K-12 career. For the first time, there was a computer in my classroom. It came loaded with some limited educational software, my favorite being The Oregon Trail. While traversing the digital prairies, I struggled with dysentery, starvation, and pixelated bears as I guided my pioneer family to our new home in the Pacific Northwest.

In the eyes of visitors, I was fully engaged in a quality learning experience with strong digital content--a happy, motivated learner. The Oregon Trail was seen by both myself and the public as an educational home run, a pioneer for what was to come in the new era of digital content.

But we were all dead wrong.

As much fun as it was, the dozens of hours I spent in class playing The Oregon Trail really only taught me what diseases people got in the 19th century. The content was disconnected from the rest of the 5th grade curriculum. My teacher couldn’t check my progress. Oregon Trail’s primary impact was not in teaching me important skills, but in keeping me from learning the things I really needed to know.

Thankfully, digital content has come a long way in the decades since I sat in fifth grade. The market has vastly improved in terms of curricular alignment, actionable data for teachers, and content quality. But if we don’t curate content judiciously, we run the risk of creating classrooms full of children skilled in digital gaming instead of children reading, writing, and understanding math proficiently. To help, I’ve outlined four guiding principles as you choose digital content.

1. Determine your specific academic goals.

The most important question to ask when deciding on digital content is: What academic goals are we aiming to achieve? Beginning with the end in mind will frame the decision-making process, focus your efforts into finding the content that will best meet your needs, and allow you to ask the right questions to ensure you know what you’re getting and why.

Common Core adoption signaled a major instructional shift in not only what was being taught, but how it was being taught. Some of the content providers in DC public schools had not yet adjusted their products to these new pedagogical shifts in Language Arts, such as engaging students with complex texts for rigorous text-based analyses, or in math, with emphases on deep understanding, fluency, and application instead of procedural, routinized instruction.

As a result, we at District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) needed to conduct a thorough re-evaluation of our existing products, and, in some cases, look elsewhere to find digital content that pivoted students and teachers on a path towards implementing these shifts.

In the 2012-13 school year, under the leadership of Chancellor Kaya Henderson (who has shown tremendous support for blended learning and technology in the classroom), DCPS began looking for digital content that would facilitate math fluency. Fluency is often taught with multiplication tables and worksheets encumbered with dozens of practice problems. However, the right digital content can provide students a chance to practice fluency while instantly scoring responses and providing feedback on both speed and accuracy--all while providing data for a teacher on student mastery.

Determining your academic goals and having a shared vision among stakeholders about the anticipated outcomes will facilitate a much more effective implementation and buy-in at all levels in the digital content. Had we solely looked for digital content that was CCSS-aligned, we’d have likely ended up with a product that failed to address the specific needs students had for fluency. In short, our students would have been no better off than they had been the year before.

2. Decide what features are important to you.

When it comes to buying a car, it’s always best to know what features you want in your new car before going to the dealership. Are power seats and four-wheel drive important to you? Or is it enough that the car has a working engine and four tires? Setting your expectations around what features you need will block out the noise from the often-unnecessary bells and whistles in the ed tech market, and can keep you from buying a lemon.

Last school year, DCPS vetted ELA digital content to support our district-wide focus on literacy. We quickly realized there were dozens of literacy products labeled as CCSS-aligned. In order to sort through all these options (our list had 48) objectively, we developed a detailed rubric that captured features that were most important to us. The rubric had broad categories (data reporting, weekly usage requirements, pricing structure, etc.) and a weighted scoring system. This gave each content provider a score that we used as a key metric in our vetting process while creating a unified vocabulary to discuss each content provider.

Our district content specialists vetted the core instruction of the programs while I looked for things related to implementation in a blended learning classroom environment. We explored questions like:

1. Is the content fully web-based, or is there an app or software that must be installed on each device?

2. Does the content require teacher supervision and support, or is there adaptive scaffolding that can support students while they work independently?

3. Can the content be modified to align with district scope and sequence documents in each content area and grade level?

4. How much professional development do teachers need, if any?

Ultimately, you should decide what features you need in your digital content and what features would simply be nice to have, and have these listed out before you start looking at content. You wouldn’t want to buy a car with fancy headlights and leather interior that also breaks down every 10,000 miles, and digital content isn’t much different. Don’t be afraid to have high expectations and ask tough questions up front—you need to know what you’re looking for to make sure you get it.

3. Go see it in action.

A 5th grade student at Simon Elementary School on ST Math (John Rice)

Websites, conference calls, presentations, demo accounts, and a rubric can all play a useful role when you’re considering at digital content, but they don’t compare to seeing the content in an authentic setting at a school. In DC, we’re fortunate to have a number of nearby district and charter schools piloting digital content and hardware that have opened their doors for us to come see how things work with students (and our doors are open to them as well). It’s one thing to hear a sales rep list the features of a given product, and quite another to watch a student use (or not use) those same features in a classroom.

For example, some ELA digital content may work well, but only when supported by a reading specialist. Other content is designed for a more hands-off approach for teachers to monitor usage and intervene when there is trouble. Knowing these factors ahead of time and planning accordingly can mean the difference in a successful implementation, and school visits are a critical component in identifying those factors. As you are evaluating digital content, ask the vendors about some nearby schools using their product, or connect with the principal or teachers there by phone or email to get some firsthand information before making a decision.

4. Make sure teachers and school leaders approve.

No matter how wonderfully engaging and perfectly aligned to curriculum digital content is, if teachers and principals don’t like it, they won’t use it. Teachers need to understand why they are being asked to use a particular program, how to incorporate it into what they are already doing, and what outcomes they can expect.

Creating a structure that allows your teachers to have input and provide feedback about the content is a critical step in selecting the right digital content for your students. Educators are rarely shy about sharing their experiences with a lesson or a product and are often willing to try something new for a brief period of time or come and learn about new products, bringing with them vast experience and the perspective from the classroom. Perhaps the product is overly difficult to log in to, or doesn’t really meet a need that teachers have in their classroom. Some of these issues can be worked through, but other times the issues indicate that it’s time to look elsewhere. In either case, listen to teachers and ensure that they find value in the content you are considering.

When students are plugged in to aligned, engaging, high-quality digital content and teachers are receiving actionable data they can use to personalize and target instruction, there is potential for truly amazing improvements gains in academic achievement. We’ve seen those gains in DC Public Schools, and we know that we are on the right track to building a district where digital content is a regular part of instruction.

However, it isn’t enough to have kids on computers playing games and spending hours on what isn’t really good instruction, like my 5th grade year with The Oregon Trail. Rather, it’s imperative that we think critically about what our goals are, curate content that supports those goals, and invest and support our teachers and school leaders in using that content to reach those goals.