One of my favorite parts of playing SimCity as a teenager was inviting Godzilla and UFOs to unleash chaos on my city.

Alas, such memorable features are not available in SimCityEDU: Pollution Challenge, an adaptation of SimCity 5 designed specifically for schools and classrooms. Licenses, which range from $3 to $20 per user, are now available through resellers.

The game was developed by GlassLab, a game studio within the Institute of Play that received $10.3 million from the Gates Foundation and MacArthur Foundation in June 2012. SimCityEDU is the first of six games that GlassLab will develop to “leverage digital games as powerful, data-rich learning and formative assessment environments,” and was built in partnership with Electronic Arts, Educational Testing Service, Pearson, and the Entertainment Software Association.

Initial Impression: Getting Schooled

SimCityEDU currently has six missions, all related to the theme of managing energy and environmental issues in an urban setting. Each mission consists of two types of activities:

- In-game: Modify a pre-built city to meet an objective;

- Concept maps: Complete a cause-and-effect flowchart that shows how variables affect outcomes. (This is all done in a web browser; there is no gameplay.)

My first in-game mission took me straight into a pre-built city, where my objective was to situate bus stops so that students could get to school. Aside from a brief tutorial on how to navigate the map with the mouse, there were no obvious instructions or directions on what the many available menu buttons would let me do.

My gamer instincts kicked in--which really meant that I clicked around the map aimlessly to see what popped up. Eventually I found the menu where I could select and place bus stops in the city. (It turns out that the game does offer hints and guidance, but only after an extended period of inactivity.)

The corresponding concept map activity for my first mission involved dragging an arrow from a circle labeled “bus stops” into a circle labeled “students enrolled.” More bus stops equals more kids at school. Ta-da!

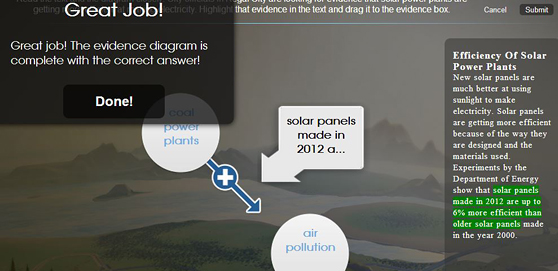

Later on, concept maps get more complex and require reading a passage and selecting the correct block of text to put into the diagram. Unfortunately, sometimes the text passages did not make sense with the visual concept map, leading to questionable logic like this:

What do solar panels have to do with coal power plants increasing air pollution?

The lack of a proper gameplay tutorial proved problematic at times. Each object in the city offers a wealth of data, from how happy the people are to how much electricity it consumes. It’s easy to get lost in the rich details. At first it was unclear what information is relevant to which objective. After half an hour, simply learning how to play the game felt like an education in itself.

In the Classroom

Getting lost in a game isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For seasoned gamers, trial-and-error is all part of the gaming experience.

But how would this play out in a classroom with students of varying gaming backgrounds and comfort levels?

I visited Lazear Academy, a charter school in Oakland, CA, where 17 seventh graders in the engineering class had been playing SimCityEDU for a month. One female student admitted that “at first, we didn’t know what to do.” But as some of the students learned the ropes, they helped others get up to speed. Throughout my visit, students were not only engrossed in the game but also exchanging strategies and tips with one another.

GlassLab product manager Liz Kline says she’s encouraged by students’ engagement. In an informal survey of 600 students, “almost all identified their experience as fun or very fun,” she says. And “replaying a level [has been] very common as students want to improve and earn higher scores.”

Many of the early-adopter teachers appear to be engaged in the online SimCityEDU educator community, too, which features an educator page with lesson plans and a Google+ page where teachers can ask questions and suggest project ideas to one another. Glass Lab producer Mat Frenz says teacher outreach has been a focus of the design and development process. Since January 2013, over 100 teachers have tested the game, which has its own “advisory council” that includes a dozen teacher and seven students.

Petrut Ababei, the first-year engineering teacher in charge of the class at Lazear, says the game has been “a useful, enrichment tool to introduce concepts” relevant to lessons he covers in class. “Some of the things that students experience in the game with mistakes and feedback are skills that apply to engineering,” says Ababei. Next to the computers where students are building windmills in the game are physical models that they have built.

Awaiting Results

Still missing from the game, however, is data on what and how students are learning from the game--a key value proposition promised by SimCityEDU and GlassLab.

The game’s web-based dashboard currently tracks how many of the missions students complete, the scores they receive, and tips for achieving higher scores. Developers say comprehensive reports, with insights such as how students navigate and solve complex problems, will be available in an update on December 6.

A larger question is whether the problem-solving skills that students develop while playing the game will be reflected in real-world knowledge, beginning with standardized assessments. The detailed brochure for the game says it covers five Common Core literacy standards for grades 6-8 around identifying and citing textual evidence to support analysis and conclusions, along with Next Generation Science Standards around “Human Impacts on Earth Systems” and “Systems Thinking.”

Evaulating how students’ in-game performance correlates with their results on standards-based assessments will be undertaken by SRI International, a R&D non-profit working with GlassLab on a larger project to research the effectiveness of games in improving learning outcomes. SRI’s first study on SimCityEDU will be released in Spring 2014.

A Tale of Two Cities

In developing SimCityEDU, one of the main design challenges Frenz encountered was: “How do you keep an open sandbox environment while keeping the game easy for teachers to implement?”

The answer appears to be sacrificing some of the open-endedness that has been a staple of the franchise. The game is less about building cities and more about modifying pre-built ones to meet objectives (like reducing pollution levels to a certain range). Each in-game mission has a 10-15 minute limit, presumably to fit within class time constraints. And the accompanying concept map activities feel more like a reading comprehension exercise than a game.

Even though the designers have made a noble effort to tailor the game for schools, technical requirements may still cause problems. The game requires downloading and installing a 1GB executable file on each machine--not an insignificant task for a lab of a dozen computers. Also, the game has certain graphics requirements appear a bit hefty. Each time I launched the game, a pop-up alert poked fun at my graphics card for being “actually pretty slow.” Granted, my three-year old PC (which runs Adobe Creative Suite and other games just fine) may be a fossil by Silicon Valley standards, but I imagine many schools may be operating even older machines.

For GlassLab, these issues in SimCityEDU: Pollution Challenge are worth keeping in mind--and cleaning up--as it develops its next game, which will focus on English language arts and argumentation skills. Its designed for tablets, set on Mars, and scheduled for spring 2014.